It's been a long time coming... I interviewed Jenni B. Baker, editor of The Found Poetry Review and the person behind the wonderful Infinite Jest poetry project, Erasing Infinite. Enjoy!

THF: Hi Jenni! Thanks for your time. Please tell us a little about yourself and The Found Poetry Review?

JBB: Thanks for the opportunity. Details of my day job aside, I’m fortunate enough to be able to maintain a relatively good work-life balance that allows me to spend a lot of my extra time reading and writing – poetry primarily. I almost exclusively work in the found poetry space, creating poems using words and phrases excerpted from a wide variety of existing texts. Most poets begin with an idea and find the words; I begin with the words and find an idea.

I founded The Found Poetry Review in 2011 after experiencing some downright dismissive and hostile attitudes around this genre of work from literary journal editors. Their misconceptions and narrow definitions of originality fueled my desire to be an advocate for erasure, cutup and other found poetry forms. To date, we’ve published more than 125 poets in six volumes of the journal, sponsored three National Poetry Month projects and issued two special online editions (including one marking the five-year anniversary of Wallace’s passing). Our poets have gone on to publish their own chapbooks and manuscripts of found poetry, and I couldn’t be more proud.

THF: What kind of hostilities and criticisms generally get directed at found poetry? Has The Found Poetry Review contributed to acceptance of the form?

JBB: There will always be a subset of editors and readers who carry a torch for “originality” and who define that term rather narrowly. What this perspective often overlooks, however, is that no poetry is ever created independent of influence. Found poetry isn’t all that different from traditional poetry – it just shows its sources.

Certainly, just as there is bad traditional poetry, there is bad found poetry. We reject more than 90 percent of what we receive over at The Found Poetry Review because some writers think the genre’s experimental foundations gives them the liberty to do things like add line breaks to a paragraph from Hemingway and put their name on it, or throw a bunch of lines together without paying attention to arrangement, syntax and voice. It’s this type of work that can give found poetry a bad name.

Conversely, good found poems possess the same qualities that make any other successful poem work – they show the same technical competencies and achieve the same emotional effect, making people think, laugh, second guess, wonder, reflect or otherwise feel something.

The Found Poetry Review is a good gateway publication to the genre, and the quality of pieces we publish increase with each issue. But I see our true measure of success as the number of our poets who go on to publish found poems in non-niche journals, and who get chapbooks and manuscripts accepted by publishers. The more poems from this genre appear in mainstream literary publications, the more acceptance it will find.

[Click here to continue reading]

HF: So David Foster Wallace... I guessing you're a bit of a fan?

JBB: I go back to that Catcher in the Rye quote about loving a book and wishing the author was someone you could just call up on the telephone. It’s rare that I see myself in the books I read and feel that the author really understands what it’s like to be inside my head. Wallace’s writing — and Infinite Jest in particular –was the first time I’d seen my thoughts, perceptions and sentiments echoed on the page in front of me. Based on my conversations with other fans, I don’t think I’m unique in that experience.

That said, I probably wouldn’t rank too high on the DFW fandom spectrum as measured by the true devotees! If Wallace were still living, I would have devoured all of his writings by now and be eagerly anticipating the next release. Knowing that he’ll never produce new work, however, compels me to moderate my reading and savor what he left behind. I have all of the books sitting on my shelf, but only allow myself to read one ‘new’ one per year. It’ll probably take me 10 years to catch up with everyone else, and I’m completely okay with that.

THF: Erasing Infinite is a found poetry project based upon David Foster Wallace's Infinite Jest. Where did the inspiration for the project come from?

JBB: Like many followers of Wallace’s work, I had a deep emotional reaction to both Infinite Jest and Wallace’s too-soon departure from the world. I sat with this abstract feeling of grief for a long time – there aren’t any self-help books or pamphlets out there that tell you how to mourn the loss of your favorite author.

I’ve always turned to poetry to constructively process thoughts and emotions, so it was natural for me to consider creative ways to express and respond to what I was feeling in regards to Wallace. One of our Found Poetry Review poets once described found poetry as “a conversation with another artist,” which precisely describes what I needed to accomplish with Wallace. I needed to have an exchange, a dialogue with him, mediated through art.

THF: Would you mind sharing a little of your creative process with us?

JBB: From the onset, I knew I needed to fracture my relationship with Infinite Jest. When found poetry fails, it’s often because the poet has produced pieces that are too close to the original in subject, style or form. Because I’m so close to the book, I knew this was a problem I’d have to address.

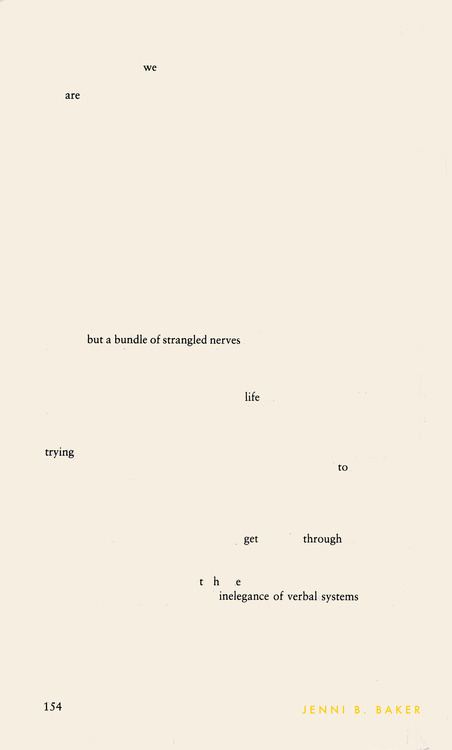

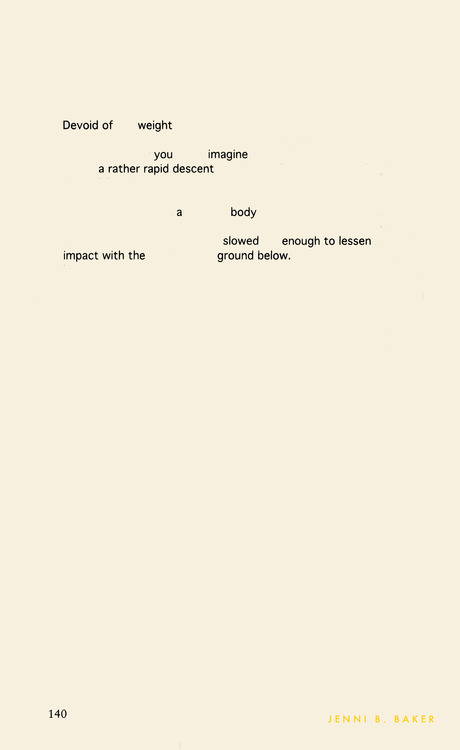

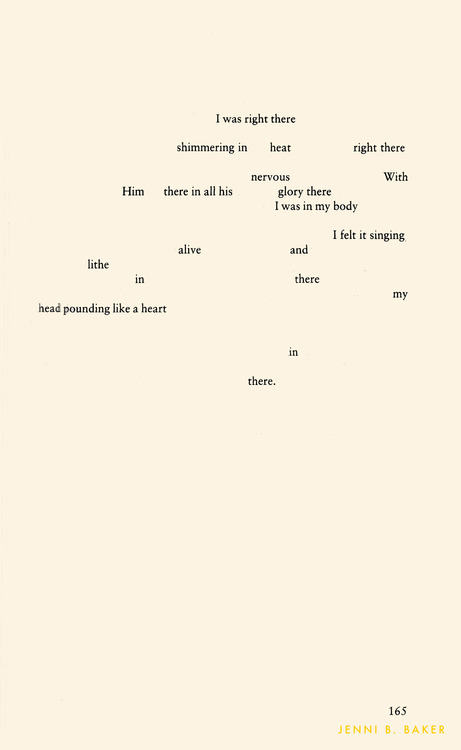

I intentionally work in the erasure format because the constraint – working with words in order as I find them on the page – forces me to sever sentences and subjects. I also present the final works as scanned page images rather than typed transcriptions; showing my work in this way ensures I don’t just find a compelling sentence or paragraph, add line breaks and call it a poem.

The other important constraint I put on myself is that I only work with one page at a time. I scan each of the pages in as a JPG, which I open up in Photoshop and look at independently without the context of the pages that come before or after. I also intentionally try not to re-read the page, to increase my odds of producing a poem that’s entirely different from the source text.

I often start by visually scanning the page in all directions, looking for interesting words and turns of phrases that I can use as a foundation for the erasure. That works about 50 percent of the time. Other times, I’ll impose additional constraints upon myself – looking only at words on the right or left columns, selecting a vertical inch of the page and only using words that fall within that space, things like that. And, if all else fails, I get up from the computer and come back later. I can spend two hours working on a page and find nothing, then come back later and spot something within 10 minutes.

THF: There has been a significant change in the project in that you no longer have images in the background of the poems. What drove that change?

JBB: To answer that, I have to start by asking myself why I chose to juxtapose the erased text with pictures in the first place.

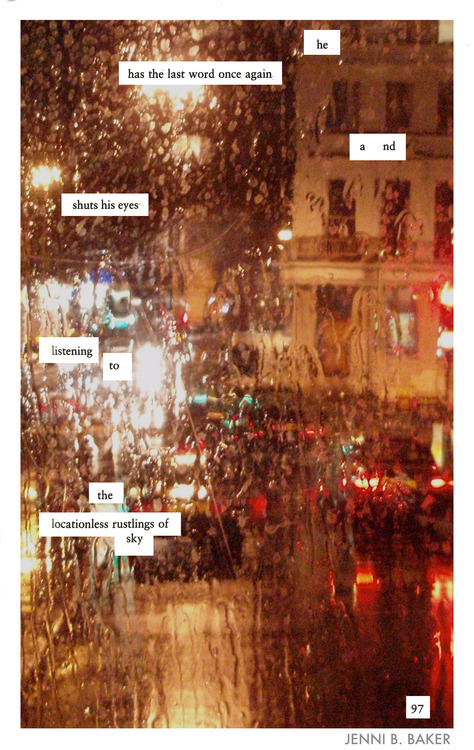

In part, it was because I was looking to attract followers as a means of gathering some external validation for this crazy project I’d been noodling on for so long. The pictures are eye-catching in a way that the erased pages alone are not, and attracted the attention of people who might not otherwise have looked at this kind of poetry. Additionally, I initially liked the idea of combining found text with “found” photos (licensed for use under the Creative Commons) and felt that the images contributed to this notion of remixing and recombination.

At this year’s AWP Conference, I was sitting in the session, “But Is It Any Good? Appropriation and Evaluation,” when one of the panelists mentioned that found and conceptual poets occasionally err in making their poems too easy for their readers. The speaker emphasized that it’s okay for poems to be challenging and to make their readers do some work to unpack them.

The conversation made me realize that by incorporating images, I was making things too simple for my readers, and that I was doing it largely out of fear that they wouldn’t otherwise understand or enjoy what I was producing. Removing the images allowed me to re-center on my process and purpose. I now put the project – not the audience – first.

THF: I certainly missed the images at first, but I think you've successfully moved well beyond them. I'm finding I focus more on the text. This is a good thing.

JBB: I’m glad to hear it. I’ve gotten the sense that the poetry and DFW communities I’m trying to connect with feel the same and understand the direction. I might have lost the attention of a few folks who just wanted to re-blog something pretty on their Tumblr accounts, but by and large, people have supported the shift.

THF: I've noticed more sharing of your project on social media and I've been emailed by many readers of this site letting me know about the existence of your project (I’ve had it in the right hand column blogroll for a while now). What's your perspective on the response to the project? Have there been any resulting creative pressures?

JBB: I read this great essay by Mary Ruefle awhile back where she said, “I love loving something so much that you simply don't care what other people think.” I try to keep that as my personal mantra, regardless of whether the feedback coming in is negative or positive.

I’m grateful and appreciative that most people have responded positively to the project. Creative writing can be a very lonely business, one that doesn’t always come with a lot of affirmation. It’s always nice to know that people are reading and enjoying your work, as long as you don’t find yourself growing increasingly dependent on their approval to keep creating.

Every project will have at least a few lone dissenters; to date, mine haven’t gone beyond issuing a few “Ugh…stupid” or “Get a life” comments on social media. And that’s okay – every piece of art doesn’t have to appeal to every single person. I invite those who take more serious umbrages with erasure poetry or my project in particular to engage with me in a more thoughtful and critical discussion.

In the face of public feedback, the main pressure I feel is to remain true to my vision for the project. It’s important to stay humble and open to the waves of feedback that may come from either direction; but in the end, I need to keep this boat moving forward.

THF: You recently announced that you're 15% through the project. Even though the end is not at all near, do you have any plans post project?

JBB: Don’t people mark significant life events with tattoos? Maybe I’ll get that little eclipse symbol from the book inked somewhere in celebration. In all seriousness, so much of this project is still unknown that I don’t dare speculate at all of the opportunities that could arise over the next few years of its execution. Erasing Infinite lends itself to a certain life beyond the web, and I look forward to exploring those avenues both during and after the project.

THF: Thanks so much for your time. Any parting comments?

JBB: Thanks for this opportunity! I also want to express thanks to those in the Wallace community who have supported the project to date and reached out to me personally. I regularly read all of the Wallace-I list serv conversations as well as what’s posted on The Howling Fantods site, and it’s a little nerve-wracking to enter as a relative outsider into such a dedicated community where individuals are regularly engaging in meaningful dialogue about an author’s work.

I’m appreciative that individuals have received the project in the spirit that it was created – a tribute and study in creative form of an author and novel that have had such a meaningful impact on all of our lives.

Want to read more? Check out Jenni B. Baker's piece over at Huff Post Books, Poetry As Tribute: Erasing David Foster Wallace's 'Infinite Jest'

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|